The following is excerpted from the introductions to IGI’s translations of al-Ghazali’s treatises Ayyuhal Walad and Concerning Divine Wisdom in the Creation of Man.

He is the Imam, the Beauty of Religion and Proof of Islam, Abu Hamid Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Ghazali of Tus, then Nishapur - the jurist, Sufi, Shafi'i, and Ash'ari.

His Birth and Upbringing

Imam al-Ghazali was born in the city of Tus, the second city of Khorasan after Nishapur, in the year 450 A.H.

Ibn 'Asakir said:

Imam Ghazali was born in Tus in the year four-hundred and fifty. He began with some jurisprudence (fiqh) there as a child. He then went to Nishapur where he attended the lessons of Imam al-Haramayn [al-Juwayni]. He strove earnestly and exerted himself until he graduated after a brief period of time. He emerged as the most discerning man of his era and singular amongst his peers. He was assigned to teach and offer guidance to students during the lifetime of his imam, and he also authored works.

The Imam would boast of him and hold his closeness to him in high regard.

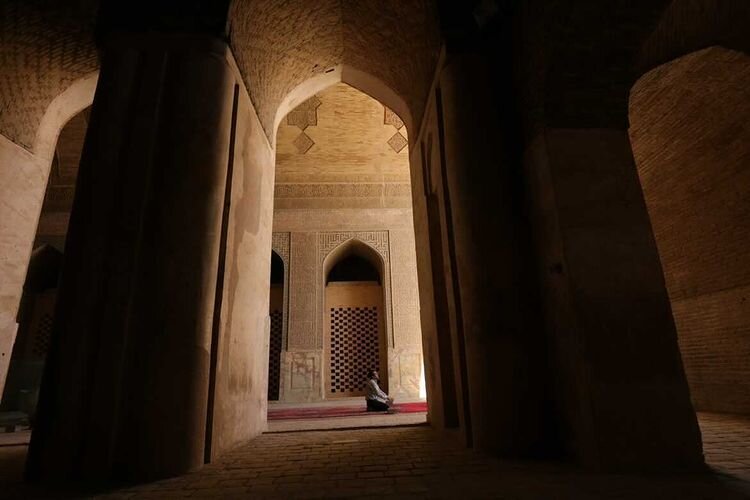

Photo courtesy of Zirrar

His Early Career

Imam al-Ghazali then left Nishapur and attended the assembly of the vizier Nizam al-Mulk. He devoted himself to it and attained a position of great importance therein due to his lofty rank and refined argumentation. The gathering of Nizam al-Mulk was the flocking place of revered scholars and the aim of imams of merit. It was there that Imam Ghazali had many chances to demonstrate his prowess in debating luminaries.

Imam al-Ghazali name became known and his fame spread. Nizam al-Mulk decreed that he travel to Baghdad in order to teach at al-Nizamiyyah, so he set out. His teaching and debating received unanimous approval whereupon he became the Imam of Iraq after having attained the status of Imam of Khorasan. His rank in Baghdad rose above that of princes, viziers, men of reverence, and the household of the Caliphate.

Turning Away from His Worldly Position

Then the situation changed, and he began to view his life from a different perspective. He left Baghdad despite his rank, pre-occupied with matters of devoutness.

In 489 A.H. he set out for Damascus and resided there a short period of time. He then left Damascus for Jerusalem. There, he began composing his book The Revival of Religious Sciences and started working on disciplining his soul, changing his character traits, improving his nature, and refining his lifestyle.

Hereby, the devil of frivolity, the pursuit of leadership and rank, and the adoption of the mannerisms of the exalted morphed into tranquility, noble manners, the abandonment of formalities and embellishments, wearing the raiment of the pious, and being undeluded by fanciful optimism. He instituted waqfs for the purpose of guiding mankind, calling them to what concerns them in the Hereafter, hating this world and preoccupation with it amongst spiritual travelers, preparing for travel to the eternal abode, and yielding to anyone who shows signs of spiritual insight or from whom one smells the fragrance of gnosis or spiritual awareness of any effulgence of beholding the Divine.

He continued as such until he became accustomed to it and relented.

He then returned to his homeland, staying home, occupying himself with reflection, and tenaciously managing his time - a rare gem that would strike terror in hearts.

Photo courtesy of Zirrar

The Status of al-Ghazali in Muslim Academia

Al-Ghazali displayed - through his writings - great mastery in Islamic disciplines in expression and in content; in image and in reality; in words and in meaning; in body and in spirit.

However, despite the unique prestige that al-Ghazali still enjoys in academia, there are scholars who find him difficult to read, and who say that his writings are full of apparent contradictions. They claim that al-Ghazali does offer any consistent foundation for some of his doctrinal positions. Some argue that this is because we cannot accurately date his writings. This prevents us from appropriating any development or change in his thought process. Others contend that this is due to the fact that al-Ghazali borrowed heavily from the language of Muslim philosophers and was thus not able to develop a language that best suited his views. Some observers went as far as denouncing him for engaging in polemics in the first place.

In general, these critics have many questions such as:

Was he in favor of learning hard sciences?

Was he against everything philosophers stood for?

Was he a diehard Ash’ari or did he lean towards a more neutral position in theology?

Was his mystical writing a mirror of his legal philosophy or vice versa?

These are some of the most common issues raised by critics regarding this great Muslim thinker and theologian.

We should add to this long list of questions a much more foundational question, which can be premised on the following notation:

Concerning Divine Wisdom in the Creation of Man, one of al-Ghazali’s lesser-known treatises, discusses human anatomy and its higher purpose. Translated by Dr. Kamran Riaz, with commentary from Dr, Riaz and Shaykh Amin Kholwadia.

Like all other Muslim scholars, we know that al-Ghazali adhered to an Islamic academic foundation in his theistic and theological writings. That is, he believed in:

The existence of one Divine Being (Allah)

The Prophethood of Muhammad ﷺ

The resurrection on the Last Day

Accepting these maxims has always been regarded as a prerequisite to enter the discourse of Islamic sciences. Conversely, only someone who explicitly denied any one of these three doctrines as essential Islamic dogma was seen as a non-Muslim. It is precisely because of this vast common ground that orthodox Muslim scholars did not go out of their way to brand unorthodox scholars as outright non-believers or apostates (murtad). Islamic law vis-a-vis apostasy (in the Sunni tradition) applies only after someone has been convicted of outrageous and obvious blasphemy. Islamic law seeks to include - but not encourage - theological aberrations as much as possible.

The question at hand is if Muslim theologians gave such latitude to religious (dogmatic) pluralism, and if al-Ghazali also believed that Muslims should not adopt any mode of ecclesiastical sentencing within the Muslim community, then why was he so adamant against Muslim philosophers that he felt compelled to write a whole book against them? Why did he feel compelled to vehemently argue against scholars who were not quite so orthodox as him? Did he feel that these philosophers - who were mostly from the Mu'tazilite sect - actually crossed the boundaries of acceptable theological views and consequently fell into kufr (disbelief)?

We hope to address these quandaries based on evaluating al-Ghazali's epistemology. We believe that unless Muslim scholars present a holistic expose of Sunni epistemology, we will not be able to appreciate the work of Sunni scholars. If we do present such an expose, we will be able to see why al-Ghazali used the language of Muslim philosophers without becoming party to their theories - as suggested by certain scholars.

On the whole, Sunni scholars were never averse to coining new terms in order to express old ideas and theories. For example, the science of `ilm al-rijal (standards by which Sunni scholars measure the integrity and reliability of Hadith transmitters) was not at all in vogue during the time of the Companions (Sahabah) of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, but became a normative science by the end of the 1st century AH.

In short, we believe that al-Ghazali should not be condemned for using a language that was different in form than the one used by traditional Muslim scholars. If he was guilty of that, then so were the traditional scholars who studied and taught Hadith. Scholars of Hadith classify several narrations from the Prophet ﷺ as being "weak" (da`if). If an unlearned simpleton suggested that Hadith scholars did not respect their Prophet since they ascribe weakness to his statements, we would all condemn him for his ignorance! We would instruct him to move outside of his operational knowledge of Islam and seek academic familiarity with Islamic sciences. Likewise, it is our understanding that reading al-Ghazali - and every other scholar - requires learning and understanding the language and idioms with which they wrote. Upon learning that technical language, which is required for reading any academic discipline (such as medicine), the student will appreciate paradigms and theories upon which he bases his arguments.

Photo courtesy of Zirrar

Imam al-Ghazali and Sunni Epistemology

Imam al-Ghazali must be seen within the tradition of Othodox Sunni scholarship. Sunni Muslims use the Companions of the Prophet Muhammad, and their understanding of revelation, as the fulcrum and pinnacle of their epistemology in primary matters of religion. By contrast, other unorthodox groups used the human intellect as an authentic standard in their epistemological framework. But both the Orthodox Sunnis and the Mu'tazilites believed in the three tools or sources of acquiring knowledge.

These three components are:

Human sensory perception (al-hawwas al-khams)

Intellectual reasoning (`aql)

Divine Revelation (wahy)

Sunni Muslims maintained that truth and certainty are perceptible if we use all three tools of acquiring knowledge in order of their authenticity and taxonomy. Knowledge gained through sense perception is indeed valid and even applicable in legal (fiqhi) matters such as the timings of prayers and rules of purity of water.

But the five senses are fallible, so we use the faculty of reason to correct and "patch up" what legal realism fails to consider and determine. But then reason also is handicapped when it comes to knowing or ascertaining truths and values that come before and after time; where universal maxims require an a-contextual platform from which to operate.

Wahy then comes to the rescue of the five senses and reason. Wahy affords us knowledge of a-contextual maxims and realities outside of time and space. Salvation then is based on employing all three tools of knowledge by confirming what wahy says; by using reason to negotiate how and where to apply wahy and by outwardly manifesting Islam through the physical body and five senses.

Shaykh Amin Kholwadia and Sidi Shoaib Malik discuss al-Ghazali’s “Concerning Divine Wisdom in the Creation of Man”

Imam al-Ghazali, as a trained traditionalist, ventured to champion the epistemology of Sunni scholars by responding to the writings of Muslim philosophers. He did this by using the language of the philosophers - which was heavily drenched in Hellenic values - to facilitate communication with them. Most of his polemical writings are focused on speaking to Muslim philosophers and not the Traditionalists, as that would have been tantamount to preaching to the choir. He always held the view that Divine Revelation should be represented only as the Ummah (the early Muslims) have understood It.

Like the Sunni theologians before him, al-Ghazali appreciated the importance of all three sources of knowledge while maintaining the primacy of Divine Revelation as the highest of these sources. But he also found usefulness in the other two lower sources of knowledge and sought to expose this utility in many of his writings. We can now appreciate his interest in various branches of knowledge that may not seem to yield beneficial knowledge to the uninitiated seeker.

We need to expand on the broader platform that Imam al-Ghazali brings to this discussion. As mentioned previously, Muslims believed there were three tools for acquiring knowledge. The purpose of this introduction is to understand how he used the first two tools (empiricism and intellectual reasoning) to launch himself further and higher so as to appreciate the third tool (Divine Revelation) and understand what the Divine says about the human body. While he had mastered the religious sciences, he ventured to look deeper into Divine Revelation (wahy) and the authentic narration of the Prophet (khabr al-Rasul) to find deeper meanings in texts that he had earlier deemed as purely legal or philosophical. This deeper insight came as a result of what he himself termed as spiritual cleansing. This power of observation allowed him to use all three tools to reach a level of understanding that was greater than the sum of its parts.

An analogy may help clarify here. Man's ability to see has multiple layers as well.

For example, on one level, physical eyesight relies on the human eye and mind to observe a chair that is present in the room.

Above this, man's intellectual eye allows him to visualize a chair in his mind without actually observing one.

Finally, the spiritual eye allows one to observe truths that are invisible and unimaginable to these other types of vision as in the case of belief in the Verse of the Chair. Muslims believe in this as an entity that is more real than real, yet no ordinary human eye has seen this nor has any ordinary human mind been able to imagine this. Therefore, because human beings cannot directly access this third level of eyesight, knowledge of this level is only through authentic narration of the Prophet ﷺ.

Once Imam al-Ghazali reached this third level of observation, he re-wrote his understanding of the physical and metaphysical worlds. The third level of observation is grounded in Islamic theology, which requires an authentic understanding of the narration of the Prophet (wahy). Muslims started to debate the methodology towards understanding theology from a very early time historically. The previous summary on Sunni theology helps us appreciate this level more appropriately.

Photo courtesy of Zirrar

Al-Ghazali’s View on the Resurrection of Human Beings

Imam al-Ghazali disagreed vehemently with Muslim philosophers who argued that the physical body will not be resurrected. Sunnis premised their doctrine of physical resurrection on taking matters of dogma as they are stated in Divine Revelation. The question then is how will our bodies function in that world (the Hereafter)?

We have seen how the understanding of the word "chair" or the perception of the word "chair" differs according to the tools used to observe it. According to Sunni belief, the perceptible ability of senses is heightened as soon as the human being departs this world. This is in contrast to Prophets who are given the ability to witness realities of the next world in this world itself.

For example, we believe that a person in the grave will perceive and understand both punishment and pleasure.

In his works, Imam al-Ghazali likens this to the perception of a person who dreams and experiences pain and pleasure in that dream. Although the dreamer has very real experiences during the dream, it becomes a secondary memory that remains, often only partially, in his mind and does not exist in his everyday life.

For the person in the grave, this perception is much higher, and the resulting pain and pleasure is much more real.

Imam al-Ghazali argues that the realities of the afterlife are to be observed through the lens of the dreamer. Similar to the dreamer, the one in the grave may feel pain and pleasure without the physical body being a part of this experience.

After this time in the world of graves (barzakh), the human being will be resurrected on the Day of Judgment. Sunni Muslims believe that the physical body will conform to the state of the spirit (ruh), allowing the senses to be heightened. If a person has lived a moral life, his body will appear in a good form. If a person has lived an evil life, his body will likewise appear in this form. However, both will possess heightened senses.

In the realm of the Hereafter, time will be expanded; this suggests that human beings' abilities will be uniquely optimized to perceive the realities of that Day and this realm. The realities of this Day and beyond are to be understood only through authentic narrations from the Prophet ﷺ. In this realm, the limited abilities of the human being in the physical world become negligible as the ruh will dictate how much a human being is able to perceive and grasp.

Photo courtesy of Zirrar

His Works

The jurist Muhammad ibn al-Hasan ibn 'Abdullah al-Husayni al-Wasiti mentions 98 authored works in his book al-Tabaqat al-'Aliyyah fi Manaqib al-Shafi'iyyah.

Subki mentions 58 works in Tabaqat al-Shafi'iyyah.

In Muftah al-Sa'adah wa Misbah al-Siyadah, Tash Kubra Zadeh mentions that his works numbered 85. He also said:

His books and epistles are beyond being counted and enumerated. No one has been able to identify the names of all of his works. It has even been said that his works are one short of a thousand, and while this would normally be farfetched, one who knows his standing might be inclined to believe it.

IGI’s translation of Ayyuhal Walad includes Wordsmiths’ elegant English rendition alongside al-Ghazali’s masterful Arabic

Dr. 'Abd al-Rahman Badawi pursued al-Ghazali’s works in his book Mu'allafat al-Ghazali and found them to be 457, of which we mention a brief few:

The Forty Fundamentals of Religion (al-Ara'bin fi Usul al-Din).

Moderation in Belief (al-Iqtisad fi al-I'itiqad).

Warding off the Masses from Natural Theology (Iljam al-'Awam 'an 'Ilm al-Kalam).

Expansive Treatment of Juristic Rulings (al-Basit fi al-Furu').

The Distinction between Islam and Clandestine Unbelief (al-Tafriqah bayn al-Islami wa al-Zandaqah).

The Incoherence of Philosophers (Tahafut al-Falasifah).

Photo courtesy of Zirrar

His Passing

Ibn 'Asakir said:

He passed onto the Mercy of Allah the Exalted on Monday, the 14th of Jumada al-Thaniyah, 505 A.H. He was buried at the outskirts of the city of Tabran. May Allah the Exalted bestow upon him all types of favours in the Hereafter just as He bestowed upon him, through His largesse, the reception of his knowledge in his worldly life.

Ibn al-Jawzi said in al-Muntazam: 'Shortly before his death, one of his companions said: "Advise me."

‘He said: "You must have sincerity", repeating this until he died.'

IGI Patrons get early access to translations and other works.

Concerning Divine Wisdom in the Creation of Man is available in the IGI Bookstore.